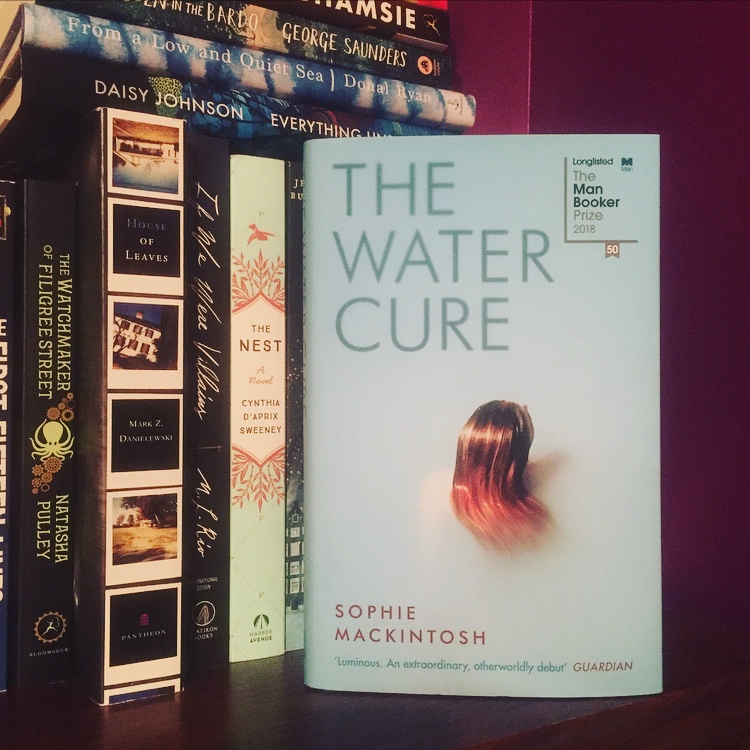

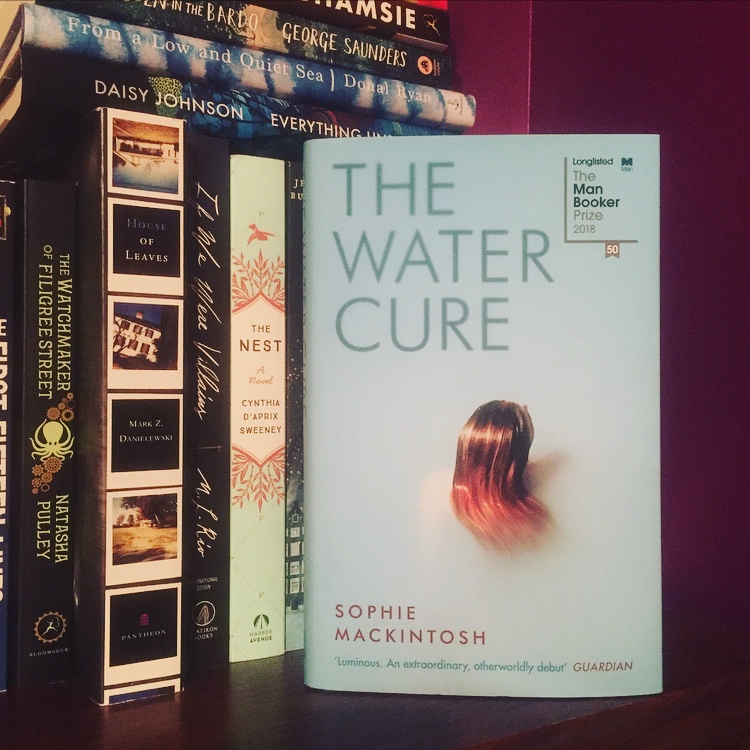

Sophia Mackintosh’s The Water Cure is Man Booker title #6 for me, and this is why I’m reading all thirteen nominees this year: because this one didn’t make the shortlist but I absolutely loved it.

About the book: Three daughters grew up on a sheltered island with only their parents and supposed “damaged women” for company. They’ve been told that the world outside their borders is full of toxins and contaminants that will harm and eventually kill them, and men are the most toxic of all– excepting their father, of course. In their little safe space, the daughters (and the women who come to them for healing) undergo daily exercises and therapies to combat the dangers of the world, including the emotions inside themselves. Young adults now, they have known no other life, but are thrust into the unknown as their family begins to break apart and men from the outside appear on their beach, seeking hospitality.

About the book: Three daughters grew up on a sheltered island with only their parents and supposed “damaged women” for company. They’ve been told that the world outside their borders is full of toxins and contaminants that will harm and eventually kill them, and men are the most toxic of all– excepting their father, of course. In their little safe space, the daughters (and the women who come to them for healing) undergo daily exercises and therapies to combat the dangers of the world, including the emotions inside themselves. Young adults now, they have known no other life, but are thrust into the unknown as their family begins to break apart and men from the outside appear on their beach, seeking hospitality.

“Strong feelings weaken you, open up your body like a wound. It takes vigilance and regular therapies to hold them at bay. Over the years we have learned how to dampen them down, how to practice and release emotion under strict conditions only, how to own our pain. I can cough it into muslin, trap it as bubbles under the water, let it from my very blood.”

I did have a few hang-ups with this book, but I was willing to overlook almost anything for the delightfully unsettling atmosphere. Complimentary elements include: otherworldy setting details, questionable narrators, mysterious circumstances, and complex interpersonal dynamics. This place is vivid.

The world outside the girls’ boundaries is less clear; it’s hard to be sure whether this is taking place in present-day, or in a dystopian future, or some other fantastical world. But I was so immersed in the girls’ lives that the unanswered questions didn’t bother me, especially because the girls themselves don’t seem to know anything factual about the outside world either.

“Every time I think I am very lonely, it becomes bleaker and more true. You can think things into being. You can dwell them up from the ground.”

Other small issues include lagged pacing in the middle while everyone in the story is basically waiting for the other shoe to drop, as well as a few surprises in the girls’ knowledge and mannerisms that don’t quite match their sheltered upbringing, and a couple of plot developments that felt a bit rushed/contrived. Any one of these could have been major issues in another book, but Mackintosh’s writing and control of her characters is so smooth and capable that the story moves quickly onward before it snags and sinks. The Water Cure is short, sharp, and to-the-point.

One of the biggest upsides, on the other hand, is the characters. Mackintosh has created this beautiful array of men and women that are not flatly likable or unlikable, but draw the reader in completely. Despite a little initial confusion while figuring out which sister was which, it quickly becomes apparent that each character is unique and built from the specific circumstances that have shaped their lives. And the best part is that it is clear that they know more than they are letting on, that they speak about healing and openness and purity but that they also contain hidden depths, their own dark secrets and an awareness of the obvious cruelty in their “therapies” that they won’t admit out loud.

Which is another plus– the cures and treatments and exercises are presented on a surface level (by the daughters) as helpful in inoculating female emotions from attachments to the men that will inevitably hurt them, but the actual dynamic between men and women, between parents and children, teachers and students is much more intricate than is shown at that surface level. There is wonderful ambiguity here that leaves the reader free to decide whether the men are toxic, whether the daughters have been fortified or damaged by their parents’ efforts, and which acts might have been borne of the very sort of love that is so expressly forbidden.

“There is a fluidity to his movements, despite his size, that tells me he has never had to justify his existence, has never had to fold himself into a hidden thing, and I wonder what that must be like, to know that your body is irreproachable.”

I was also fascinated by the interspersed entries from the Welcome Book that the girls peruse, entries written by the women who come to the island in search of healing and cures. Some are more specific than others, but all speak to the specific hurts of women. These sections do not further the plot, but they do add to the atmosphere and serve as a reminder that much of the girls’ knowledge of the world outside of their home has been gleaned second-hand from people seeking to escape it.

“It’s an old story and I’m so tired of telling it– the oldest story in the world and yet I can’t put it down, I can’t stop it from dragging on my body, so don’t make me tell it again. The story doesn’t end or even begin with me. You can imagine. You can tell it to yourself.”

So darkly dreamy. Brutal, and yet the reader floats through the story.

My reaction: 5 out of 5 stars. I had a wonderful time with this weird little book and can’t wait to see what Sophie Mackintosh writes next. Next for me on the Man Booker list is Washington Black, and from there I’m planning to focus more on the shortlist titles I haven’t read yet before rounding out the longlist.

My Man Booker reviews (listed in order of most to least favorite): Everything Under, From a Low and Quiet Sea, The Mars Room, Warlight, Snap. If you read and loved The Water Cure (or plan to), I also recommend picking up Daisy Johnson’s Everything Under, another short, dark, magical novel; this one made the shortlist.

What’s been your favorite Man Booker read this year (from the 2018 longlist or any previous winners/nominees)? Or any others up for awards that have caught your eye?

Sincerely,

The Literary Elephant

In the novel, a picturesque Californian town becomes a news sensation when the perplexing case of one girl who can’t be woken turns into an epidemic of sleeping citizens. At first the “sickness” is confined to a single dormitory floor at the local college, but the dreams (and the students) defy containment. One by one, the young and the old drop off to sleep and are essentially lost to the living.

In the novel, a picturesque Californian town becomes a news sensation when the perplexing case of one girl who can’t be woken turns into an epidemic of sleeping citizens. At first the “sickness” is confined to a single dormitory floor at the local college, but the dreams (and the students) defy containment. One by one, the young and the old drop off to sleep and are essentially lost to the living. About the book: Three daughters grew up on a sheltered island with only their parents and supposed “damaged women” for company. They’ve been told that the world outside their borders is full of toxins and contaminants that will harm and eventually kill them, and men are the most toxic of all– excepting their father, of course. In their little safe space, the daughters (and the women who come to them for healing) undergo daily exercises and therapies to combat the dangers of the world, including the emotions inside themselves. Young adults now, they have known no other life, but are thrust into the unknown as their family begins to break apart and men from the outside appear on their beach, seeking hospitality.

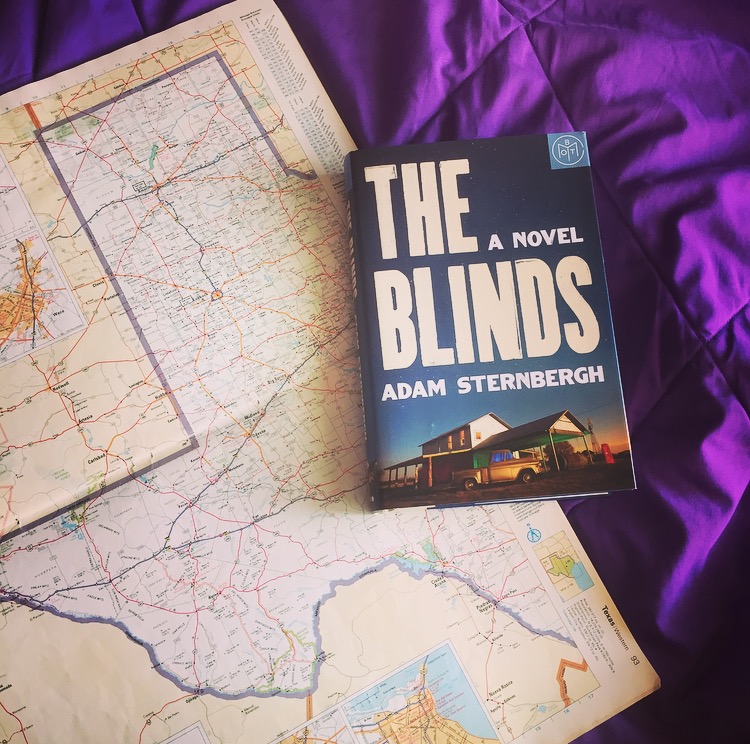

About the book: Three daughters grew up on a sheltered island with only their parents and supposed “damaged women” for company. They’ve been told that the world outside their borders is full of toxins and contaminants that will harm and eventually kill them, and men are the most toxic of all– excepting their father, of course. In their little safe space, the daughters (and the women who come to them for healing) undergo daily exercises and therapies to combat the dangers of the world, including the emotions inside themselves. Young adults now, they have known no other life, but are thrust into the unknown as their family begins to break apart and men from the outside appear on their beach, seeking hospitality. About the book: Caesura, Texas– aka The Blinds– is an experiment. 48 convicted criminals have signed on to have their past crimes and traumas wiped from their memories so that they can live in the “safe” environment of Caesura, under new names. 100 miles from civilization, with only a weekly supply truck and a police-use fax machine for contact with the outside world, Caesura has been constructed specifically for this experiment. But eight years after its inception, the experiment may be falling apart. There are deaths. Fires. Vandals. Liaison officers are coming in to investigate, and the outside world is clashing with the closed-off Caesura community. What happens when 48 of the nation’s most notorious criminals who remember their criminality but not their crimes are nudged out of their comfort zone?

About the book: Caesura, Texas– aka The Blinds– is an experiment. 48 convicted criminals have signed on to have their past crimes and traumas wiped from their memories so that they can live in the “safe” environment of Caesura, under new names. 100 miles from civilization, with only a weekly supply truck and a police-use fax machine for contact with the outside world, Caesura has been constructed specifically for this experiment. But eight years after its inception, the experiment may be falling apart. There are deaths. Fires. Vandals. Liaison officers are coming in to investigate, and the outside world is clashing with the closed-off Caesura community. What happens when 48 of the nation’s most notorious criminals who remember their criminality but not their crimes are nudged out of their comfort zone?